The Hidden History of the Civil Rights Act of 1960

You might be asking: “Was there a Civil Rights Act of 1960?” Yes indeed there was. And it was quite significant, but only if understood through the convoluted system of voter disfranchisement during the era of Jim Crow. The Civil Rights Act of 1960 helped prove racially, discriminatory voter-registration practices and provided evidence used to help pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This post explains how and why.

The Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 were the first pieces of federal civil rights legislation passed since Reconstruction. Initially conceived to better enforce the 14th and 15th Amendments, the 1957 Act was met with fierce resistance from southern white segregationist senators. During months of hearings and debates—including the longest filibuster to that point in the Senate’s history—the bill was effectively stripped of concrete federal mechanisms to enforce school desegregation or protect southern Black voting rights. The most important accomplishment of the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the establishment of a (then) temporary investigative unit named the Commission on Civil Rights and the creation a new assistant attorney general for civil rights.

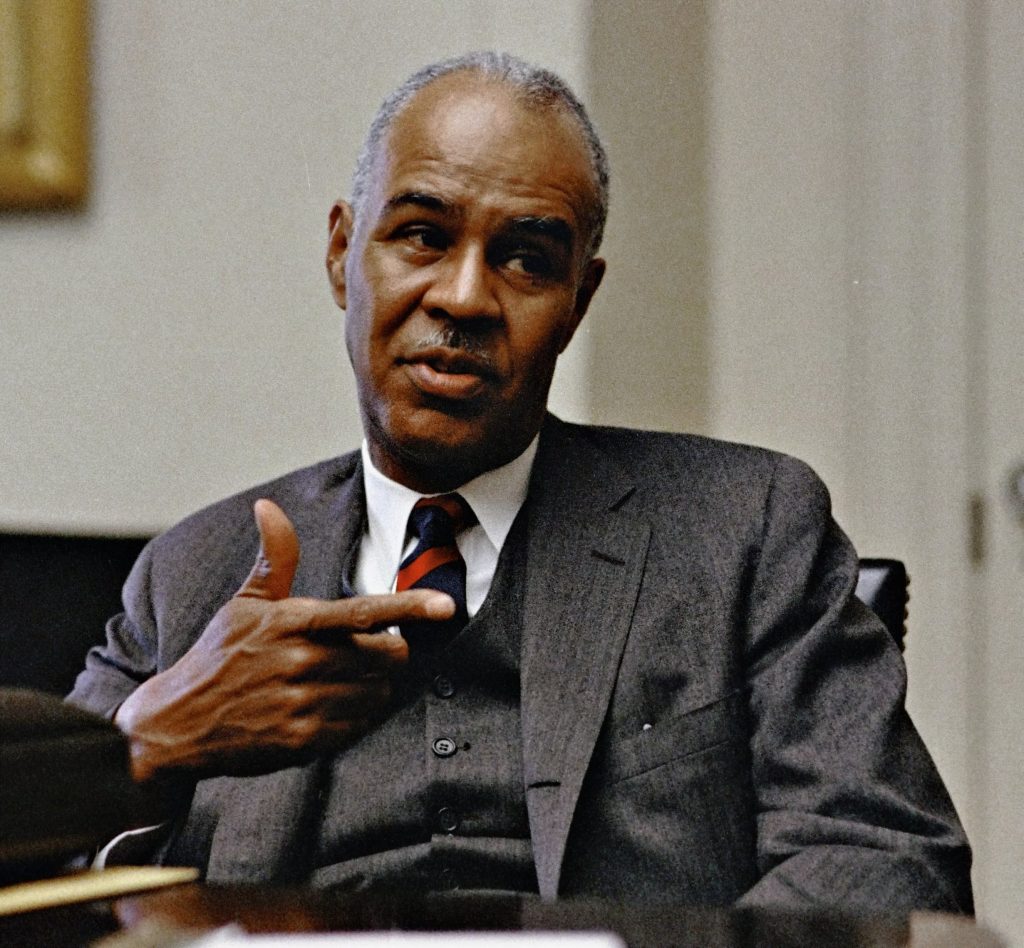

African American pundits immediately criticized the limitations of the 1957 bill. Journalist Ethel L. Payne, the “First Lady of the Black Press,” called the final version a “battered, almost unrecognizable version of the civil rights bill passed by Congress after virtually all the teeth had been pulled.” A Chicago Defender editorial concluded, “this legislation proves to be much weaker than we had previously expected.” And NAACP leader Roy Wilkins later labelled the act “A Small Crumb from Congress.” Even Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, who helped usher passage of the bill, famously acknowledged the legislation as “half a loaf” of bread. Although some have celebrated the historical significance of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, historians have largely agreed with the sentiments of its contemporaneous critics, generally concluding that the bill was ineffective and unenforced, except in a few rare instances.1

Believe it or not, the Civil Rights Act of 1960 has received even less acclaim. Similarly weakened by white southern senators, this bill was designed to remedy some limitations of the 1957 Act. Although it received widespread bipartisan support among northern lawmakers, more than a year of hearings and “Southern Hacking”—as one reporter described—resulted in another law devoid of concrete mechanisms to enforce school desegregation and convoluted by a set of amendments concerning court orders, property damage, and the education of children of military families. The 1960 Act did introduce the idea of federal voting referees to remedy racially based, voter discrimination, but the burdensome procedure of appeal required individuals to navigate a complicated process and furnish their own proof that race was the deciding factor in the denial. “We may as well have no Civil Rights Act,” lamented the Chicago Defender the following year, “if its provisions are unenforceable.”2

Historians have offered just about the most damning treatment possible to the Civil Rights Act of 1960: benign neglect and disregard. There are entire books about the Civil Rights Movement and voting rights in modern America that do not even mention the legislation. Lyndon B. Johnson biographer Robert Caro has suggested that the bill was “at best, the smallest of steps forward—and it may have even have been a step back.” The Civil Rights Act of 1960 was indeed disappointing. Past and present critiques are certainly valid. But historians operating with hindsight have consistently underappreciated one crucial aspect of the Civil Rights Act of 1960 that significantly affected the struggle for Black voting rights.

Remember that the 15th Amendment outlawed racially based voter discrimination. A series of southern state laws—especially literacy tests and poll taxes—developed near the turn-of-the-twentieth century to disfranchise African Americans, circumvented this. It is now widely recognized that these mechanisms were used explicitly to prevent Black people from voting during the era of Jim Crow.

But during that era, arguments over literacy tests and poll taxes were quite different. In the 1940s and 1950s, white southern segregationists offered alternative explanations for the astonishingly low numbers of registered Black voters. During subcommittee hearings for the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, white southern politicians fought against stronger voter protection mechanisms by arguing that Black people were either unqualified or undesiring of voting. The literacy tests and poll taxes, they claimed, were merely tactics used to ensure that only engaged and qualified citizens of any race could register to vote. The strength of their argument lay in the fact that white voters also had to complete literacy tests and pay poll taxes and that poll taxes were not uniquely southern. They could also always point to a very small number of registered Black voters in any county as proof that some Black people could register to vote, if they so desired.

During the same hearings, voting rights activists attempted to refute these claims with evidence that indicated racially based voter discrimination. These included NAACP reports, affidavits signed by people whose voting rights had been denied, and personal testimonies in front of a House subcommittee. Witnesses who testified in the legislative hearings encountered white southern segregationist politicians determined to refute the validity of their lived experiences. In one example from 1957, North Carolina Senator Samuel Ervin cross-examined a Black Mississippian named Gus Courts who had been shot in retribution for voting rights activism. This witness could have removed his shirt to display his wounds to anyone in the room. Nevertheless, Ervin badgered Courts, questioning the validity of his claim and trying to discredit the Black witness with irrelevant questions about his federal taxes. Ervin even questioned the details about the timeline in Courts’s account of being transported to the hospital after being shot. Such was the experience of Black witnesses in Washington D.C. Their testimonies—even when backed by absurdly low voter registration figures—were never enough to verify racially based voter discrimination. The Civil Rights Act of 1960 offered a new apparatus to acquire additional evidence.3

Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1960 required “every officer of election” in the United States to “retain and preserve” all voting-related records for twenty-two months and to produce these records “upon demand in writing by the Attorney General.” The Act was signed into law on May 6, 1960. Over the next sixteen months, Attorney Generals William P. Rogers of the Eisenhower administration and Robert F. Kennedy of the Kennedy administration requested to inspect voting records in twenty-six southern counties where African Americans had alleged discrimination. Inspection of these voting records revealed critical evidence that proved racially based voter discrimination. But not in the way one might assume.

The issue raised by these inquiries concerned not only who was denied the right to vote, but also who was given that right and by what process. The records of southern registrars revealed starkly different voter registration processes explicitly linked to the race of the applicant. Some registrars did not require white people to take a literacy test at all. Other documentation showed that white and Black applicants were consistently asked different questions in literacy tests. Most provocatively, some records showed that illiterate white citizens passed literacy tests. There were white people listed in the voter registration books who had signed their name by leaving the mark “X.” Further interviews with unsuspecting white voters confirmed evidence found in the voting records. In at least one Mississippi county, the local registrar had never denied a single white voter applicant, proving beyond all shadow of doubt that white and Black voter applicants faced different standards based on race.4

Based on this evidence, the Department of Justice filed nineteen voter discrimination cases by the end of 1962—all of which contributed further to the mounting evidence that Black people were denied the right to vote based on race. When debates over southern voting rights reemerged in the House in later years, voting rights activists were equipped with overwhelming evidence of racially based voter discrimination that proved the need for federal oversight to enforce compliance with the 15th Amendment. The Civil Rights Act of 1960 aided in that process by providing the Department of Justice with an additional tool used to investigate voter procedures in places where African Americans had told of voter discrimination.

The roots of 1960s-era voting rights victories lay not in a dramatic moment on an Alabama bridge or in personal relationships between civil rights movement leaders and politicians, but rather in the efforts of thousands of brave Black men and women who risked their lives and livelihoods by attempting to register to vote and then testifying about that discrimination to disprove the lies of white southern segregationists.

- Ethel L. Payne, “Ok Patched Up Civil Rights Bill,” Chicago Defender, September 7, 1957, 1; “Our Opinions,” Chicago Defender, September 28, 1957, 10; Roy Wilkins and Tom Mathews, Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins (New York: Viking, 1982), 221-246; and Johnson quoted in Robert A. Caro, Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon B. Johnson (New York: Vintage, 2002), 1003. ↩

- Robert C. Albright, “Southern Hacking Continues,” Washington Post, April 4, 1960, A1; “Civil Rights Act,” Chicago Defender, August 14, 1961, 11; Steven F. Lawson, Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944-1969 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), 203-249. ↩

- Senate Subcommittee, Civil Rights—1957; and U.S. Senate, Civil Rights—1959: Hearings before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Part 2, 86th Cong., 1st sess. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1959). ↩

- United States v. Lynd, 349 F.2d 790 (1965), Brief for Petitioner, Box 1, Folder 13, Gordon A. Martin Jr. Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi. ↩